1: Muharram marks the massacre of the grandson of the Prophet, Imam Hussain (ع), alongside his entire family, after they refused to pledge allegiance to the oppressive rule of the corrupt Yazid. Yazid had usurped control of the Muslim caliphate a few generations after the Prophet’s death. After Hussain responded to calls by the people living under Yazid’s rule for liberation, he and his family traveled to Karbala in southern Iraq, where they were chased and hunted down by Yazid’s armies who cut off their access to water. On the tenth of Muharram, (known as Ashura), Hussain was killed after being given the option for a final time of choosing between acknowledging Yazid’s rule and death.

The sun was just setting on the third day of Muharram, finally providing relief from Chicago’s unforgiving heatwave. One by one the streetlights slowly flickered on and the smell of incense drifted around us. All dressed in black and marching together, we were carrying the weight of the lives stolen from us as we chanted demands for a future that would bring justice in their memory. Many of our bodies were sore and bruised from the nights before. A drumbeat kept our pace while others offered food and water or carried massive black flags and other symbolic items above them.

This was a Black Lives Matter protest. But for me, it was also my first Muharram1 procession.

2: For all intents and purposes the line between the police and white supremacist groups are quite blurred, as there is substantial overlap in personnel and purpose.

Spending time “in the streets” these past two months, amid what Angela Davis has called “unprecedented” uprisings in cities across the United States, has redefined my relationship with mortality itself. Death has become so much more intimate, tangible, palpable, and with it therefore, my sense of proximity to, and near-constant awareness of, divinity and the world after death. As a non-Black person living in the US, I have had the privilege of being able to take my sense of “safety” for granted (for the most part). But in the last few months, safety has, to some degree, become a relative and fluid concept, one I can no longer foresee or predict, especially when trapped between an overfunded and trigger-happy police force swarmed around us with riot gear and tear gas, batons raised, and the armed white supremacist group we were just alerted are now on their way.2

As such, the conscious decision to get dressed and race to the police precinct after receiving a text at midnight from a friend on the ground saying “Natl guard just arrived. Wearing gas masks & heavily armed. They’ve boxed us in. Come now” is a simultaneous acknowledgement—whether consciously or not—that the justice and future we’re collectively fighting for is more important than the safety of our physical bodies, which we will all leave behind at some point. It was not simply a responsibility to my friends and everyone beside them at that moment, but more importantly an obligation to participate in Imam Hussain’s unfinished uprising; an attempt to manifest—rather than simply recite—the legacy of our ancestors whose stories are re-told (and erased) every year. Death is inevitable, but justice in this world is not.

Imam Hussain’s (ع) legacy at Karbala was just that: “death with dignity is better than a life with humiliation.” In other words, justice takes precedence over our lives—a notion antithetical to our modern-day carceral state or capitalist “values” on human life, focused so clearly on the here and now, and a fear of a death that separates one from their wealth.

Of course such a proximity to—and being on the receiving end of—this State violence is scary and emotionally and mentally taxing. But there is something deeply spiritual about the experience which forces one to reckon with mortality, and therefore the consideration of what comes next. As Muslims, we are encouraged to rehearse dhikr, a repetition of words or phrases that serve to remind us of the divinity in our lives. In doing so, this rehearsal is a form of spiritual grounding; a release of this world for a reminder of the next. So then how much more deeply enveloped in God’s mercy and love are those whose everyday is the very embodiment of this remembrance of the divine? How deeply powerful and divinely blessed are the everyday lived experiences of Black people in particular in the U.S. (and truthfully, globally) whose very existence, joy, and love–let alone leadership in continuing Hussain’s unfinished uprising–is in and of itself a form of resistance to racial capitalism and its violence that attempts to erase the divine?

This in its essence is a form of liberation theology: a way to reject the fears of this world (death, man, poverty, etc) for a prioritization of the next.

To borrow from Iesa Lewis’ beautifully-written piece “A Reflection on Revolts:“

“In the modern logic of slavery, we perpetually see that bodies are subjugated and enslaved, that those conditions of slavery dictate and regulate behavior, and ultimately that whiteness is glorified and even deified…Allāh tells His creation to seek refuge in Him from these forms, to turn to Him and Him alone. The ‘Word/Testimony of Oneness’ (kalima al-tawhīd), what makes the Muslim a Muslim, Lā ilāha illa Allāh, is a sufficient philosophy of liberation. Inscribed in its everlasting power is the statement to man; “you are not god.”

… [T]he Islamic imperative is that we complement the negation of deities, the ‘lā ilāha’ [there is no God], with the affirmative statement ‘illā Allāh’ (except Allah)…we must reject the Western anthropocentric tradition that places ‘Man’ at the center of the universe – everything is about our rights, freedoms, and individual interests. Instead, we must renew the Islamic vision of God first, such that liberation is complete submission to Allāh.”

It is with this Islamic liberation theology, lā ilāha illā Allāh, that the legacy of Ashura is clearly understood and we are forced to ask ourselves difficult questions that re-frame life, death, and fears for us outside capitalist framings. When being called to the streets to demand justice, what are we more afraid of than God? What could possibly be more terrifying than the wrath of the all-powerful? And what is more beautiful than the love of the most-merciful? Is our goal to survive—a goal that cannot be ever achieved—or to do what is right so that our souls can transition to the next world with blessings? If, as we are told in the Qur’an, that at the end of our time on earth we will look back on our lives and it will feel like only an afternoon (79:46), what then are the equivalent of a few extra minutes on earth if they are not in pursuit of what is right? For many Muslims like myself and as exemplified during Muharram, seeking God is synonymous with seeking justice.

And as all stories which serve as revolutionary models for and by the oppressed, Imam Hussain’s story at Karbala has been largely erased from many (primarily non-Shia) Muslim spaces. Many commemoration marches around the world are actively criminalized and have even been targeted by ISIS and others enacting anti-Shia violence. On August 29th, Indian military forces occupying Kashmir (the most densely militarized region in the world) opened fire with pellet guns on a Muharram procession, injuring dozens. The fact that India has banned major Muharram processions in Kashmir since the 1989 armed uprising against India’s occupation speaks volumes as to the types of parties invested in this erasure and criminalization.

Others degrade the memory of the Prophet’s family by saying that Shias “are still crying over something that happened over 1400 years ago.” This only serves to indicate a clear lack of understanding of both the history of Muharram and contemporary politics.

The tragedy of Ashura did not happen over 1400 years ago. It happened on May 25th, 2020; October 20th, 2014; March 21st, 2012; August 28, 1955; and it will happen again in the U.S. every time another Black person is killed by the police or vestige of slavery.

As poet Nouri Sardar recites in his poem 72 verses for Imam Hussain, “You’ll know how a man lived by how he died.” And Imam Hussain died like George Floyd, Muhammad Muhaymin, Laquan McDonald, Rekia Boyd—as a martyr of a State crackdown on resistance: whether through an uprising or simply “resistance by existence” while Black in a racial caste system.

It is in this essential justice-seeking that Imam Hussain’s revolt not only provides for us a blueprint of the struggle that needs to be continued, but it is in the commemoration and remembrance of Muharram that we can find a decolonial rubric of healing, community organizing, and vision building.

There is one important element that is quite globally shared in Muharram commemorations: collective grieving. Central to Muslim observations of Muharram are the re-telling of the story of Hussain’s uprising while attendants, and oftentimes the speakers themselves, audibly cry. Did you even commemorate Ashura if you didn’t cry? The scholar Shereen Yousuf writes:

“…our communal grief serves as a radical act…I find that tears can heal the communal body as they would an individual body, in that tears garner the potential to cleanse us of the toxins named fear, shame, doubt, anxiety and guilt, that reside in the crevices of our minds, hearts, and souls. In fact, these very emotions of inferiority are what permits these modes of domination over us to begin with, and it is tears [that] grant us the space to heal from them.”

A “decolonial” (and, dare I say “feminist”) practice of crying is at its core a refusal to become numb and desensitized to, violence. It is a refusal for men to be ripped from their ability to express the full range of human emotion without feeling “emasculated”, a refusal to normalize and contend with ever-present violence and Black and brown death, and a refusal to continue life as “business as usual” in spite of it all.

It is a decolonizing practice of self-preservation and care, and especially so for those living with a system designed to commodify, profit from, and maintain their/our oppression. Rather than indulging in unhealthy coping mechanisms such as compartmentalization or denial (or celebrating capitalists of color as “hope”), taking a moment to reflect on, engage with, and allow yourself to become (even if only momentarily) overcome by the reality of the suffering potentially ever-present in our lives, neighborhoods, communities, and ancestors, allows us both a release and grounding reminder of the urgency of justice. Practices of communal crying can be critical for our movements’ longevity and personal healing.

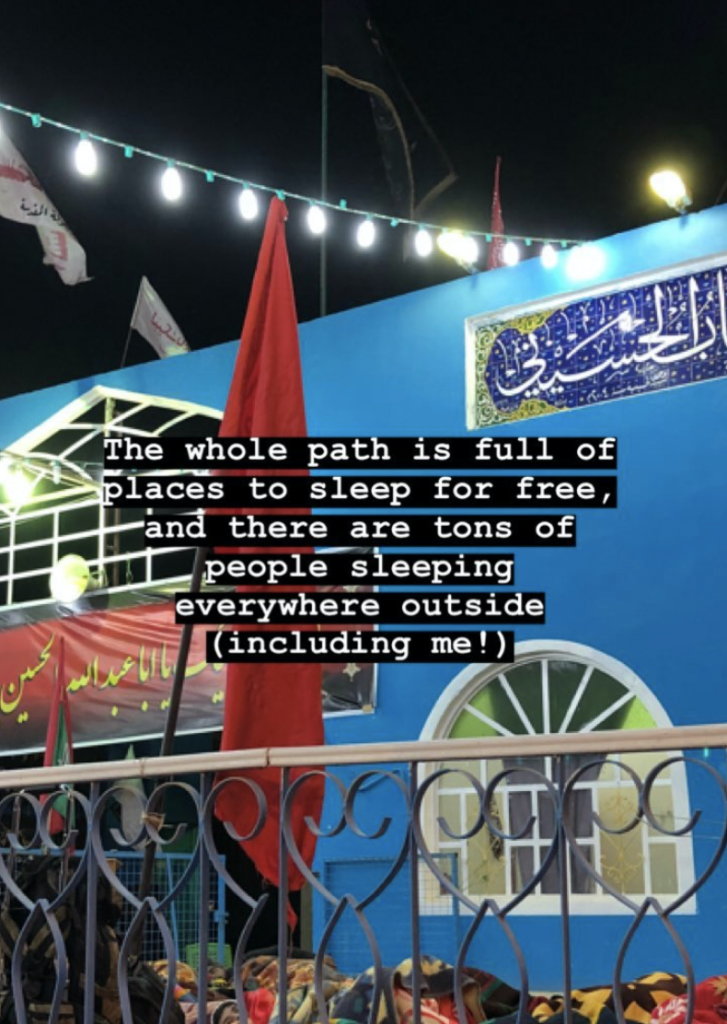

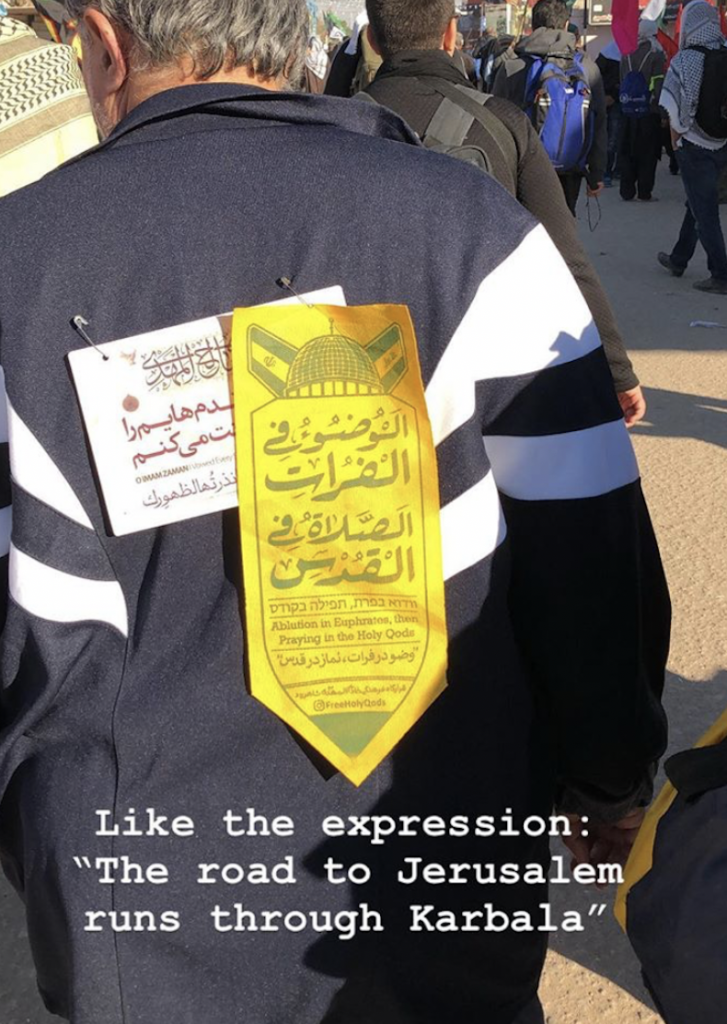

Even more broadly, beyond collective grief, the radical tradition of Muharram can be most clearly witnessed every year during the Arbaeen pilgrimage to Karbala, which takes place 40 days after Ashura. For two weeks, Muslims from around the world come together to walk 57 miles on foot from Najaf, Iraq to Karbala, following the final journey Imam Hussain and his caravan made. Every year more than 20 million people attend, making it also the largest pilgrimage–and autonomous and grassroots-organized mutual aid network–on Earth.

Photos above c/o Alex Shams, taken in 2019

Every day during the two week journey, every single one of the millions of participants hailing from around the globe are fed (with full meals, tea, and sweets from around the world), given shelter, and cared for (including even booths for foot massages) without a single dollar (or dinar) exchanging hands. There are also theatre-like re-enactments along the way of the events of Muharram (known as taziyeh) that serve to retell, embody, and internalize Hussain’s uprising.

Many of these traditions also exist and have been ongoing in a parallel manner in the United States: the massive food distribution may recall the Black Panther Party free breakfast program under their “Revolutionary Services” branch, and the value of independent community building outside of State markets as a pillar of the Nation of Islam. Much like the taziyeh and its role in embodying Hussain’s revolt, New Orleans Black activists host an annual Slave Rebellion Reenactment, “retrac[ing] the path of the largest rebellion of enslaved people in United States history, embodying a story of resistance, freedom and revolutionary action.”

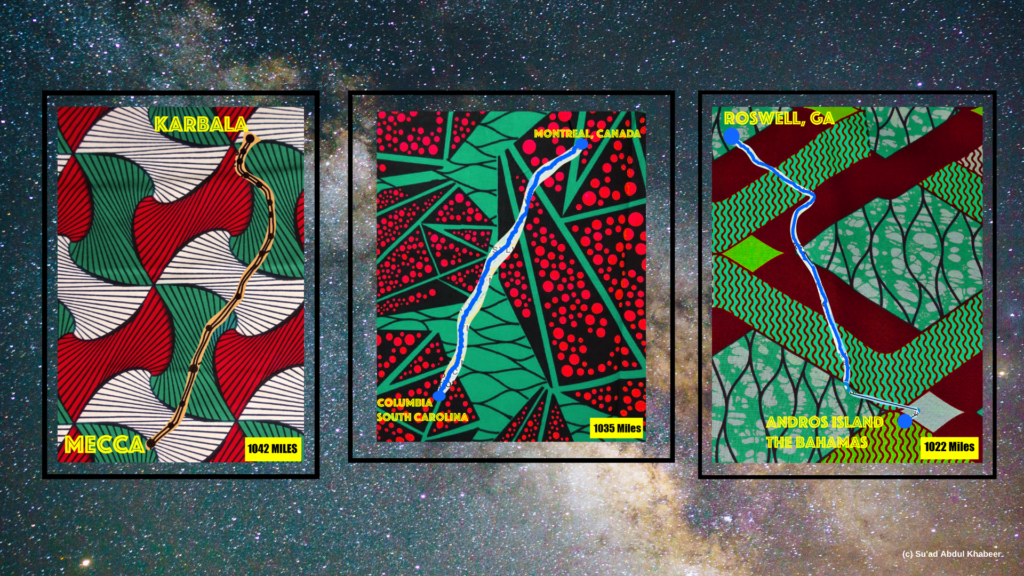

In fact, just last week the scholar Dr. Su’ad Abdul Khabeer juxtaposed the route of Imam Hussain with the routes of the Underground Railroad that Black people followed to freedom:

These parallels are not simply a coincidence, but a manifestation of a liberation framework shared, rehearsed, passed down, and inherited by oppressed people globally. Black people, and particularly Black Muslims are, and have been, consistently leading these movements in the United States. While the particularities of each of these revolutionary services, re-enactments, routes to liberation, and historical moments are distinct from one another, they each are passing on and inheriting both the modes of resistance and the underlying power dynamics, racial and economic caste, and state oppression that seeks to undermine lā ilāha illā Allāh

Taken in a broader, global perspective, these collective and internalized practices have proved to be able to be quickly activated in order to serve tangibly revolutionary moments outside of these spaces. In Iraq’s (unfinished) uprisings last Fall, the same people who had travelled annually to Arbaeen to feed hundreds or thousands of people within the span of a few days were now feeding the thousands on the streets demanding their freedom.

And it is this translation of embodied rituals practiced, rehearsed, and grounded in Islamic tradition to service toward liberation movements seems to be at the very core of the events at Ashura and the commemorations that have followed.

Imam Hussain and so many of our role models, within the Islamic tradition or otherwise, were rebels and outsiders: those seeking justice within an unjust system and world. If they lived in the contemporary United States, they would likely be incarcerated, or dead. So what does this mean about these systems we find ourselves in if the best among us would be considered criminals, and the worst among us are elected as the leader of this country?

A truly honest reading of the life of Imam Hussain and tragedy of Ashura provides us with the lessons and guidance that many of us—myself included—may not be entirely ready to hear. But this moment in particular that we have found ourselves in has made devastatingly clear the urgency to not only hear the challenges we are called upon to respond to, but to actively respond to them.

Arundhati Roy says the pandemic is a portal; so too can be each moment of our lives. It is in these moments when we are asked to resist, revolt, and rise up, potentially risking our lives or bodily harm, that we decide who we are, what we believe in, and whose side we’re on.

Movements are waves, and, to borrow the phrasing of Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “a rehearsal of revolution.” Much like the repetition of praying five times a day, a tangible practice and discipline that connects us to the divine, so too is our embodied practice of collectively demanding justice—whether through a Muharram procession or a BLM march, or both together.